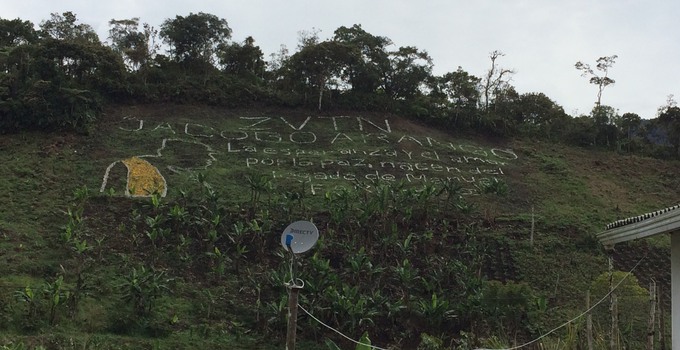

A mural in Caño Indio in northeastern Colombia illustrates the shared identity between the guerrillas and the farmers. Photo: Private.

Feminist struggle after life in FARC guerrilla

The peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrilla in 2016 meant that guerrilla soldiers returned to civilian life. Priscyll Anctil Avoine has examined what the transition has meant for the women who were part of the FARC, and how they have transformed armed struggle into a feminist struggle.

At the end of 2016, after years of negotiations, the Colombian government signed a peace agreement with the country's largest guerrilla group. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia—People's Army, abbreviated as FARC-EP in Spanish, was one of the oldest left-wing guerrillas in South America. The agreement entailed a commitment that all thousands of guerrilla soldiers, both men and women, would lay down their weapons and rejoin civilian society.

For the women, the transition posed both challenges and contradictions, but also an opportunity to transform the armed struggle into a feminist struggle. This is discussed in the research article "Farianas’ insurgent feminism: for a militant, affective and embodied reincorporation in Colombia" published in the scientific journal European Journal of Politics and Gender. The author is Priscyll Anctil Avoine, an associate lecturer at the Department of War Studies at the Swedish Defence University.

"I wanted to show that there are many contradictions for the women, which are different compared to what the men experience. Women are accused of abandoning their children during the guerrilla wars, which men are not. Women are expected to devote themselves to caregiving now after the peace agreement. I wanted to explore how they can continue their political struggle," says Priscyll Anctil Avoine.

Breaking conservative norms

Farianas is a name for women who have been part of the FARC, either as active guerrilla soldiers or engaged in activities supporting the FARC. During the peace negotiations between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrilla, a subcommittee was created to ensure that the agreement would take gender equality issues and women's perspectives into account. According to Priscyll Anctil Avoine, this enabled women in the FARC to launch their own vision during the negotiations: insurgent feminism.

"Within the framework of the peace agreement, many questions arose about the role of women in the FARC. From that discussion, women started a feminist education within the FARC, and they launched a website. It was their first step towards claiming an identity as farianas. Today, not all women claim their identity as farianas; it varies and is something that is debated," says Priscyll Anctil Avoine.

Between 2019 and 2022, she conducted ethnographic fieldwork in northeastern Colombia. Based on her experiences in the field and recurring interviews over several years with women who have been part of the FARC, she has examined their experiences, and what significance it has had to retain the rebellious as a political stance.

"With reintegration, the goal was to normalize people, to get them to return to a certain civil status. Insurgent feminism becomes a way to continue fighting, but without weapons. My question was, how do they transform armed struggle into a rebellious struggle for feminism? And how is it expressed?"

Challenging norms as a member of FARC

Like many other countries, Colombia is characterized by strong patriarchal values, and for some women, joining the FARC offered better opportunities than they had in their home villages. For instance, many appreciated that in the guerrilla, they had the same functions as male guerrilla soldiers and that everyday chores were shared equally.

"FARC is not outside the patriarchy, but the women felt that they could challenge the norms within the framework of the armed struggle."

At the same time, life in the FARC guerrilla was demanding and harsh, in various ways. The norms of the guerrilla included that women were expected to agree to avoid becoming pregnant.

"FARC is a very disciplined army, very hierarchical. So, regulation of bodies is important. If you want to start a romantic relationship, for example, you must inform the commander about it," says Priscyll Anctil Avoine.

The picture was taken in the province of Dabeiba, Colombia, and shows a message written with white stones, "La esperanza y el amor por la paz nacen del legado de Manuel, Farc-ep," along with an image of Manuel Marulanda Vélez, on of the founders of Farc-ep. Photo: Private.

Returning to traditional roles after guerrilla life

The transition to civilian life after years in the guerrilla forces elicited various emotions and reactions from the women. Surrendering their weapons was experienced as an internal rupture and a breakup. One of the guerrilla soldiers told Priscyll Anctil Avoine that the weapon felt like a part of her body.

"The weapons were synonymous with their survival. Handing them in and returning to civilian society became an emotionally embodied break with their previous lives."

Some experiences were the same among men and women, but a significant difference was that women, after guerrilla life, were expected to adopt traditional female roles. They were supposed to engage more with the private sphere, focusing on family and motherhood, caregiving, and nurturing..

"They say, 'we always lived together, and now we must learn to live in a house with a key and a partner.' They are expected to adapt, to normalize themselves by coming into our world. But is it good? To what kind of society are the guerrilla soldiers being reintegrated?"

Many felt nostalgic about their time in the FARC guerrilla and felt they had lost community, friendship, and camaraderie. They also felt anxious about the new civilian everyday life and the future, where life had now become a much more individual project than before and where a happy life was defined differently—often associated with a heteronormative life in a nuclear family.

Feminist movement in development

Despite it being eight years since the peace agreement was signed, women still live under difficult circumstances in Colombia. The return to civilian life seems to have even led to an increase in violence against women, especially against leaders of environmental and feminist movements.

"The peace agreement has not been implemented well. Despite this, women continue to mobilize and fight. The Farianas have something important to contribute to the creation of peace, against oppression. They have a special experience of war that can teach us a lot, such as questioning our views on gender structures," says Priscyll Anctil Avoine.

The Farianas see insurgent feminism as an emerging movement. Some are trying to influence within the political party Comunes, founded by the FARC guerrilla, while others have left the party. There are tensions both between different groups of Farianas and within the party—and between other feminist movements and the Farianas, according to Priscyll Anctil Avoine.

"In Colombia, feminist struggle has always been linked to the anti-militarist movement, and Farianas have certain difficulties finding their space in this context. Their constant work and political struggle have nevertheless made it possible to build important alliances and continue working for an unarmed insurgent feminism," says Priscyll Anctil Avoine.

Publication

Farianas' insurgent feminism: for a militant, affective and embodied reincorporation in Colombia, published in the European Journal of Politics and Gender.

More about

Page information

- Published:

- 2024-11-18

- Last updated:

- 2024-11-18